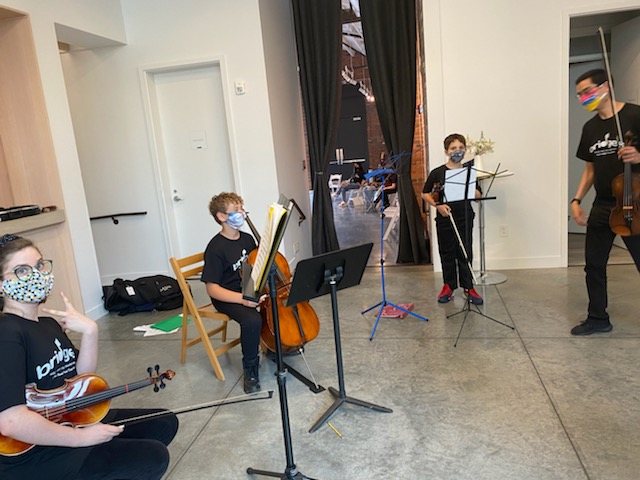

Bridges focuses on bringing together young string players from homeschooled, public, and private educational backgrounds, working to “bridge” the socioeconomic divide through accessible programs. In Summer of 2021, we met at outdoors chamber music sessions, coming back together after a long period of quarantine from the COVID-19 pandemic (see performance below). Learning in community and making live music together after having to restrain to online interactions for over a year, became priorities above the search for skill advancement and canonic standards of excellence.

Bridges MAYO + cumbia

Bloomington IN (USA) + Colombia

Listen to our first performance of «Colombia Tierra Querida» by Lucho Bermúdez:

In learning Lucho Bermúdez’s cumbia «Colombia Tierra Querida», in arrangement for string orchestra by Esteban Hernández Parra, the Bridges students had conversations about the Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous roots of the genre, how the rhythm and dance patterns came from the resistance of enslaved west African people, and how Indigenous instruments like the gaita were used by Zenú, Kogi and Kuna peoples before colonization from the Spaniards.

Here are the score and parts to the cumbia arrangements our Bridges students learnt:

From my experience working within academic institutions like elementary beginning public strings and pre-college programs linked to universities both in Colombia and the U.S.A., I have sensed a generalized lack of exposure to rhythmic training that is not “squared” -avoiding syncopation and polyrhythms- which is characteristic of methods based on Western music; all this though approaching learning in a heavily individualistic way.

Here I offer some pedagogical resources and reflections on how to approach the cumbia feel, through engagin emotionally with sabrosura through this arrangement. Sabrosura comes from the word sabor (flavor), it does imply a certain “taste” related to someone’s style. It is a colloquial term used to denote contagious enjoyment when engaging in an activity. In music it has a similar “indescribable” feel as groove, it is not taught but learnt through emotional connection. Similarly to el Vivir Sabroso it brings together joy in community, especially related to interconnected social activities such as cooking, eating musicking and dancing.

Embodying the sabrosura in Afrodiasporic genres like cumbia through singing and dancing can not only stimulate a more diverse understanding of rhythm but connect students emotionally with the practices and struggles of the people who have -and continue to- preserve and develop these musics. It is a more effective and empathic way to learn and feel these rhythmic intricacies in community, to approach them through collaboration. This resonates with Afrodiasporic philosophies like el Vivir Sabroso, where supporting each other, caring for, and dignifying life is done though communal enjoyment.

In reflecting about my initial conversations about cumbia with the Bridges MAYO students, I realize at the time I did not delve into a matter of class in the appropriation, by the middle/upper-class elites, of this Afroindigenous cultural tradition. This is the reason why around the mid-twentieth century jazz/big band cumbia style like Lucho Bermúdez’s became increasingly popular in urban areas of the country (cities like Bogotá, where I am from). This problematizes my positionality as a musician from Bogotá, since I first learnt about this cumbia in particular through symphonic orchestra arrangements; I continue to find ways to approach teaching this piece in a more ethical and responsible way.

After three years and other work on different pieces of Afrocolombian music like the pasillo chocoano I will be discussing below, we performed the cumbia “Colombia Tierra Querida” again in 2024 through a much more successful, robust, and enjoyable learning process. You can even hear our beginning students playing the percussion base of cumbia in this video!

Here is a short clip on how I shared the cumbia history and dance in our 2024 performance:

Esteban shares cumbia story and dance steps

During the same year Bridges’ students first started learning the cumbia, Leonidas Valencia Valencia, Colombian musician, pedagogue and researcher, published Repertorio Musical del Pacífico para Formato Cámara “KILELE”. In his digital compilation, Prof. Leonidas arranged a broad variety of traditional genres from the Pacific coast of Colombia for string ensemble (Violin, Viola and Cello), in his own words, “… [arranging] these musics from the Pacific in such format, aims to serve musical education centers of any level, experimenting texture, accentuation, articulation, and metro-rhythmic varieties of great utility in pedagogical and ensemble activities within the musical practices of the country” (Valencia, 2021, p. 5)

Santiaguito + Bridges

Chocó (COL) + Bloomington IN (USA)

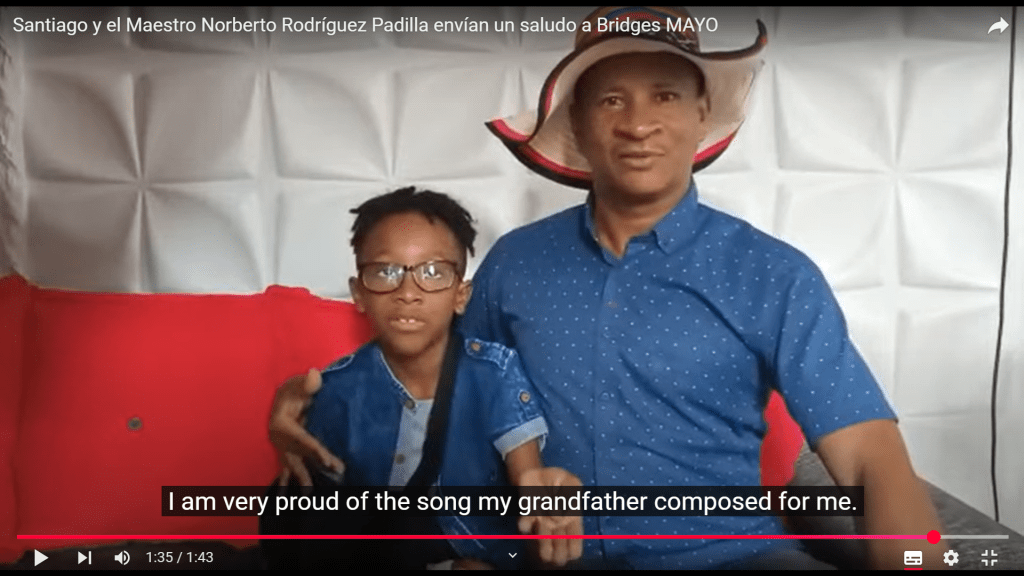

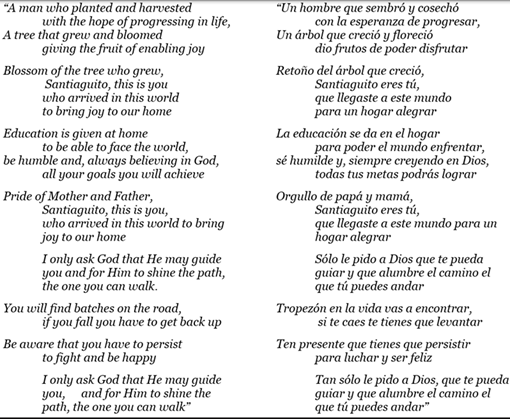

Maestro Norberto Rodríguez Padilla from Tanguí, mid-Atrato, Chocó, Colombia, protects, dignifies, and blesses the life of his grandson, Alex Santiago, through this Grandfatherly love made sound

«Alex Santiago Rodríguez Agudelo is a seven year old boy … he is the joy of our home» says Norberto, composer of this pasillo, when refering to his grandson.

«Santiaguito” is a pasillo chocoano originally performed by Tanguí Chirimía, an Afrocolombian ensemble with over two decades of artistic career. The instrumentation of Chirimía in the Chocó region includes voice, clarinet, saxophone, bombardino (baritone horn/euphonium), tambora (bass drum), redoblante (snare drum), and platillos (cymbals) (Valencia, 2009). The version we performed with Bridges MAYO in Bloomington was a string orchestra arrangement by Prof. Leonidas Valencia Valencia with edited parts by Sarah Maggie Olivo. Leonidas’ work as an Afrocolombian musician, researcher, and activist, makes otherwise possible (Crawley, 2017) to share the love, resistance, and sense of belonging that Norberto, Santiago, and Tanguí Chirimía put into “Santiaguito.”

Bridges 2023 orchestra plays Santiaguito in the track below

The Bridges MAYO students and I learnt and performed this pasillo chocoano within an environment of relationality made possible by Norberto’s generosity and care, and Maggie’s role and mobility outside academia. Her trajectory as an educator in both public school system and university elementary music programs, as a facilitator of collaborations through the Fairview Violin Project, Bloomingsongs and Dan Kusaya’s Zimbawean marimba workshops, Maggie has become a fundamental community organizer in the Bloomington musical scene, which allowed for an approach of mutual solidarity within Bloomington to make possible the connections with the cultural bearers in Colombia.

My pedagogical approach to integrate certain embodied practices towards performing with a particular sabrosura (groove). Passed down through oral tradition and preserved by cultural bearers like Norberto Rodríguez Padilla, director of Tanguí Chirimía, the Afrodiasporic influence in this genre is deeply interconnected with dancing, singing, collective resistance, community care, and racial healing.

Sabrosura comes from the word sabor (flavor), it does imply a certain “taste” related to someone’s style. It is a colloquial term used to denote contagious enjoyment when engaging in an activity. In music it has a similar “indescribable” feel as groove, it is not taught but learnt through emotional connection. Similarly to el Vivir Sabroso it brings together joy in community, especially related to interconnected social activities such as cooking, eating musicking and dancing.

By focusing on rhythmic and affective qualities in these musics, I will explore how otherwise embodied learning practices, defy the power dynamics normalized through draconian traditional conservatory methods (Musumeci, 2002); with a pedagogy of sabrosura I intend to honor and hold space for Afroindigenous practices that conjoin the acts of learning and teaching within otherwise possibilities (Crawley, 2017).

Historically, “music literacy configured a privileged scenario to legitimize Eurocentric cultural values, above other values proper to Afrodiasporic culture” (Valencia, 2009, p.14), therefore performing directly from a resource arranged by a cultural bearer like Prof. Leonidas was an opportunity to continue learning Afrodiasporic musics through a decolonial approach.

I will now offer context through a video recording, scores, instructional materials, and the details on the pasillo genre present in these stories and files below:

The following link contains the edited parts to Santiaguito, arranged by Leonidas Valencia and edited for youth string ensemble by Maggie Olivo:

The resources discussed in this entry on “Santiaguito” can be used by educators and performers to contextualize the piece for student populations who have not been in contact with pasillo chocoano traditions. Maestro Norberto has generously agreed to share the materials to teach and perform his music at no charge, his interest is for more people to have contact with his music.

More from Tanguí Chirimía: